What does it mean to be “a New Testament Christian?” Last Sunday we considered the 4-pronged formula Paul gave in Philippians 4 for living an abundant and victorious Christian life: 1) always rejoicing in the Lord; 2) replacing anxiety with prayer and thanksgiving; 3) dwelling on the positives, that is, things that are true, honorable, right, pure, lovely, of good repute, of excellence and worthy of praise; and 4) learning to be content regardless of our circumstances. Today, in his letter to the church at Thessalonica, Paul writes some of the most glowing words of commendation that he ever penned to any of his churches. The Thessalonians appear to have been persons who modeled Christian living at its best. He writes that they have become “an example to all the believers, not only in Macedonia and Achaia, but also in every place (where their) faith toward God had gone forth, so that (he had) no need to say anything.” Of course this is Paul writing, and it turns out that he had rather a lot to say: things about his suffering and shameful mistreatment at Philippi, things about the Thessalonians’ eager acceptance of his Gospel message, words about how to walk and please God even more, and instruction about the return of Christ and the Day of the Lord.

But first Paul offers these amazing commendations in words that would rejoice the hearts of God’s people anywhere. Just the three things he mentions in verse 3 would be enough to trigger what our Jewish friends call “kvelling,” swelling up with justified pride and gratitude. Paul praises their “work of faith,” their “labor of love” and their “steadfastness of hope,” all of which are rooted in “our Lord Jesus Christ in the presence of our God and Father.” And it’s on this basis that Paul states his knowledge that they are “beloved by God” and chosen by Him. We think of the concluding words of Jesus in last week’s Gospel reading, “Many are called but few are chosen.” Paul can assert confidently that the Thessalonian believers are among God’s chosen, as evidenced and indeed proven by the fact that his “gospel did not come to (them) in word only, but also in power and in the Holy Spirit and with full conviction.”

Paul likes to state things in threes, and here we’ve had two such groupings: first the Thessalonians’ “work of faith, labor of love and steadfastness of hope,” then their reception of the Gospel message “in power and in the Holy Spirit and with full conviction.” “Work of faith” is a very clear expression of Paul’s consistent teaching about faith. For Paul, while salvation required the articulation of core beliefs, faith itself was an active concept, so that “work of faith” could almost be heard as a redundancy. Faith, by its very nature, works. It works itself out. It expresses itself in action. Faith is not a Sunday morning thing where we gather together with persons who agree with us and then go our separate ways to live “normal” lives while waiting for our next time to be together. No, for Paul, faith is equated with the Christian’s way of life. The Latin Fathers picked up on this when they spoke of our “regula fidei,” our rule of faith, which is found in the creeds but lived out on a daily basis. The Thessalonians understood this concept and put it into practice in such a way that it provided an example “in every place (where their) faith toward God had gone forth.” It was not their doctrinal statement that was going forth; rather it was their faith in action, their “work of faith.”

Then Paul adds their “labor of love.” We could think that this was just a reinforcement of the first phrase, that “work of faith” and “labor of love” are basically the same thing. But to say that is to forget the things Paul so clearly expressed in I Corinthians 13, the great “love” chapter that is read at so many Christian weddings. There Paul writes that “if I have all faith so as to remove mountains but have not love, I am nothing” (v. 2). And he concludes, “So now abide faith, hope and love, these three; but the greatest of these is love” (v. 13). Paul makes this sharp distinction between faith and love. As Christians who call ourselves “evangelicals,” we need to take care that our pride in orthodox theology does not begin to take the place of our calling to be persons who live out the love of Jesus Christ in our everyday lives and witness. May the love of Jesus be seen in us as it was in the “labor of love” in which the Thessalonians engaged.

And third there’s the “steadfastness of hope,” something that suggests the believers at Thessalonica were living out their expectation of Christ’s return. In the final two chapters of this epistle Paul will give them some instruction about their hope and its proper foundations, twice exhorting them to encourage and build up each other with their forward-looking perspective. Paul was writing to the Thessalonians not more than 20 years after the Resurrection and Ascension of Jesus, and expectations remained high that His return was imminent. After telling his readers to encourage each other with those expectations, he adds that they already were doing so. Now 2,000 years have passed, and we rarely hear any mention of Christ’s return in the context of encouraging the faithful. The modern church is seldom likely to be commended for its “steadfastness of hope.” But from God’s perspective, from the perspective of eternity, the return of Messiah is just as imminent today as it was in 51 AD. And we should be living in that expectancy and encouraging one another with it. Christ is coming, and we pray always that it may be soon.

Then there’s the second trilogy in these verses, where Paul affirms that his preaching of the “gospel did not come to (them) in word only, but also in power and in the Holy Spirit and with full conviction.” “Power, the Holy Spirit and full conviction” form a compelling triad of ways to hear and live out the message of the Gospel of Jesus Christ. We often lament the lack of power in the Church today and its ever-diminishing influence in our secular culture. Yet we do so little individually to demonstrate the power of the Gospel. We leave it up to “the Church,” forgetting that we are the Church in this world. Institutions do not have power without people.

The power of the Gospel lies in the fact that it changes lives first and, only after that, changes societies. It’s been a long time in our country since the Christian faith has exercised spiritual power or has been instrumental in establishing a spiritual power base through which God’s Word can make a difference in the way we live, in the way our leaders govern and in the way we function in the world.

Former President Obama was right when he declared that America is no longer a Christian nation. We bristled when we heard him say that, and we wanted to claim that it was his own distorted opinion. But he was absolutely right. And who do we have to blame? Not Mr. Obama for his diagnostic skills. We have ourselves to blame, not just corporately but individually, because we have meekly surrendered our power base by failing to live our lives in the power of the Gospel.

Second there’s the Thessalonians’ reception of the Gospel in the Holy Spirit. Here Paul comes closer to a redundancy than he did when he juxtaposed “work of faith” with “labor of love.” For the believer, the Holy Spirit is the only true Source of our power.

Today we like to emphasize the power of personalities, bigger-than-life individuals who exercise power in ways that more often are frightening rather than inspiring. We see power as something that resides in governments and military might. The Church certainly is not an institution that springs to mind when we’re discussing power structures. There are still religious leaders who periodically raise their voices, but they’re not persons who wield any real power.

There was a time in the history of the Western world when the Church did indeed exercise power; but we all know how that went. The power that the Church is meant to exercise is not political power per se; rather, we are to exercise Holy Spirit power. Where is Holy Spirit power in the Church today? We tend either to ignore it or to fear it, worrying that the Holy Spirit just might make demands on our lives to which we remain fiercely resistant. If too much is required of us, we’re far more likely to run away than to submit. It’s the way we’re wired.

But that’s solely because our wiring is controlled by our society and our “old natures,” rather than by the Holy Spirit. We leave the Holy Spirit to “those charismatic people,” whose expressions of Christian faith are too “over the top” for us. But that’s very far away from the perspective of Jesus Himself and of all the New Testament writers. There is no single greater need in the Church today than Holy Spirit power. We could use more education, more theological acumen, more foundational truth, more faith, more love, better music. But what we need above all is Holy Spirit power, without which all the rest is without context and without real power. We need power, but we have a serious power outage in the Church.

Third and last, Paul mentions “full conviction.” I will confess before I say another word that this is by far the hardest one for me to address. I’m profoundly impressed by Paul’s unhesitating readiness to commend the Thessalonian believers for their “full conviction.” I would love nothing more than to be able to turn the calendar back 2,000 years and catch a plane to Thessalonica just to see what it was like to have a church filled with those who could be characterized as persons of full conviction.

Be really serious for a moment with me and, more importantly with yourselves, and ask yourselves how many Christians you know that are persons of “full conviction.” Let’s look first inside ourselves and ask whether we are persons of “full conviction.” What might our lives look like if we were? What differences would there be in the way we spend the rest of our time today after we leave this beautiful building? This is the Lord’s Day, and we tend to give Him as little of it as possible. We think that an hour and a half should be more than ample to appease the God Who gave His only Son for all of us, for our sins, for our redemption and for our eternal life with Him. What differences would there be in the way that you spend the next 6 days before you return here if your lives were driven by full conviction? If you were to walk out of here this morning saying that you would act as a believer governed and driven by full conviction, eagerly and routinely accessing the power of the Holy Spirit, fully engaged in the work of faith and the labor of love coupled with the steadfastness of hope, would your life be the same as it is right now? Seriously?

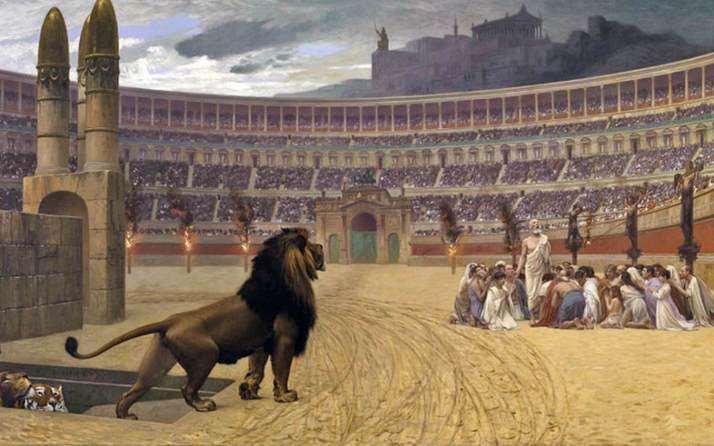

Why were the believers in the early Church so deeply committed to living out their faith? Why were they willing to risk martyrdom every day of their lives? Why did St. Iganatius, a disciple of the Apostle John whose feast day was this past Tuesday, eagerly embrace the likelihood that he would be fed to the lions in the Coliseum of Rome, as in fact he was? Why were the early Christians willing to leave everything behind to be followers of Jesus and proclaimers of the Gospel message? As Paul himself put it in personal terms, it was because the love of Christ constrained him. It compelled him. It controlled him. He said, “Woe is me if I preach not the Gospel” (I Corinthians 9:16).

What is the context of Paul’s statement that he was compelled by the love of Christ? Just listen to this verse from II Corinthians 5:

"For the love of Christ controls us, having concluded this, that He died for all, so that they who live might no longer live for themselves, but for Him Who died and rose again on their behalf" (v. 10).

What would it mean for us no longer to live for ourselves, but for Him Who died and rose again on our behalf? Every one of us would experience differences in our lives. We would experience for ourselves just what Paul goes on to say in the verses that follow:

Therefore if anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation; old things have passed away; behold, new things have come. Now all things are from God, Who reconciled us to Himself through Christ and gave us the ministry of reconciliation, that is, that God was in Christ reconciling the world to Himself, and He has committed to us the ministry of reconciliation.

Therefore, we are ambassadors for Christ, as though God were making an appeal through us; God made Christ, Who knew no sin, to be sin on our behalf, so that we might become the righteousness of God in Him. (vss. 17-21, edited)

What does it mean for us to be “a new creation,” to be “ambassadors for Christ,” to be “the righteousness of God,” to live “no longer for ourselves?” It means everything. It means a life sold out to God and His work. It answers all the hypothetical questions we’ve just asked. The rest of today would be different. The next 6 days would be different. Your life would not be the same as it is today.

Do you really want to be a Thessalonian Christian, a New Testament Christian, the sort of Christian of whom Paul was so justifiably proud? Being a New Testament Christian is very different from being a 21st century Christian. It requires everything of you. But it’s what’s asked of all to whom God has committed the ministry of reconciliation. It’s what the love of Christ compels us to be and to do as His new creatures, as persons being re-made into the image of Christ, the One Who loved you and gave Himself for You. He asks you to give all of yourself in return. May we respond ever more fully to what He wants us to be, every moment of every day.

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, Amen

Only to be what He wants me to be,

Every moment of every day,

Yielded completely to Jesus alone

Every step of this pilgrim way.

Just to be clay in the Potter's hands,

Ready to do what His Word commands

Only to be what He wants me to be,

Every moment of every day.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed