Our former rector at Church of the Holy Spirit in Lake Forest used to start out his sermon every Trinity Sunday by saying that it was the only Sunday in the entire liturgical calendar that commemorates a doctrine rather than a person or an event. I suppose that he may have been right in a manner of speaking, but not really quite right: what he said was more amusing and attention-getting than accurate. Trinity Sunday, in one sense, commemorates a Person more than any other Sunday. It commemorates God, God in Three Persons, the blessed Trinity. It commemorates a mystery, to be sure; but the mystery has everything to do with the Godhead Whom we worship. And while many people might stay home if the preacher announced in advance that he would be explicating a mysterious doctrine next Sunday morning, some visitors might actually come if word got around that he was going to explain in plain terms the mystery of the Trinity. At the least it could stir up some curiosity.

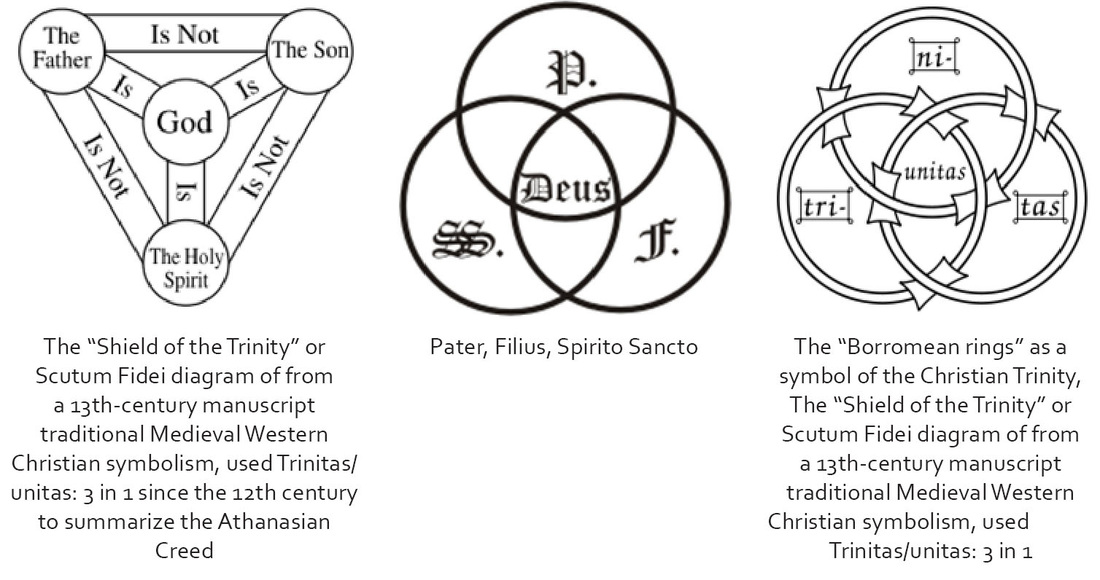

I would love to think that by the time you leave this morning you will fully comprehend the doctrine of the Trinity and rush out to write everything down and convey it to all your friends, Christian or not. But this will not happen. The most I can hope for is that you will go away having thought more deeply about the Trinity and having come at least a little closer to understanding why it is absolutely at the center of a Christian understanding of Who God is, how God acts and how He relates to us both corporately and individually. Two traditional ways of visualizing the Trinity are the triangle and the three concentric circles (see below).

Backing up a lot, in the OT there are two names of God that occur with greater frequency than any other: the Hebrew 4-letter name that we call the tetragrammaton and that Christians generally pronounce as Yahweh or Jehovah or simply Lord (though it would be less confusing if we could reserve “Lord” for the Hebrew word Adonai), and the word commonly translated as “God,” which in Hebrew is Elohim, the first name for God that appears in the Bible: Genesis 1:1 – “In the beginning God (Elohim) created the heavens and the earth.”

It is very important to recognize that the name Elohim is plural, as is also the name Adonai. There are a variety of possible explanations for why this is the case. One is the rather unsatisfactory syncretistic idea that ancient pagans worshiped many gods and so, too, must have the ancient Hebrews, a theory that cannot begin to explain the almost fierce monotheism of Judaism. Another is the thought that Elohim is simply the plural of divine majesty, sort of analogous to the “royal we” used by many monarchs of the past. But a third idea is that God has existed eternally in a plurality of being that suggests internal fellowship and economic division of labor within the Godhead. This last understanding is essential to the Christian doctrine of the Holy Trinity, and it is the very thing that absolves Christianity from the charge of being tritheistic.

The devout Jew recites the Shema from Deuteronomy 6 every single day, both morning and evening: it begins with these 6 words: Shema Yisrael Adonai Elohenu, Adonai echad (“Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God is one Lord”). But of these very Hebrew words, 4 out of 6, including the word for “one,” echad, all admit of plurality: both Adonai and Elohenu are plural to start with, and echad, to give just one obvious example out of many in Hebrew, is the word used in Genesis 2:24: “And they” (referring to a married couple) “will become one flesh” (basar echad). Obviously this is the ideal that God desired when he created humans: plurality in unity.

In Genesis 1:27 we read the familiar words, “God created man in His own image, in the image of God He created him; male and female He created them.” But in the bond of marriage, the two become “echad,” bringing them even closer to the image of the God in Whom plurality is embedded in His very nature. After all, in the immediately preceding verse, Genesis 1:26, we read, “Then God said, ‘Let Us make man in Our image, after Our likeness.’” Matthew Henry, author of one of the most widely read commentaries on the Bible, wrote:

“God said, Let us make man. Man, when he was made, was to glorify the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Into that great name we are baptized, for to that great name we owe our being.”

Before God created Eve from Adam, He said, “It is not good that the man should be alone; I will make him a helper fit for him” (Genesis 2:18). Man alone did not fulfill or complete our creation in the image of God. It had to be male and female, two who become one. There had to be plurality in order for there to be fellowship. And fellowship is absolutely fundamental, again, to Who God is and how God acts.

Those who argue against the concept of God being One in Three always point out the absence of one single verse or passage in the Bible that explicit states the doctrine of the Trinity. Yet the NT is full of statements that can be understood in no other way than on the basis of a Trinitarian concept of the Godhead. Obviously the most important of these is what we call “The Great Commission,” given by the resurrected Christ to His disciples, where He tells them to baptize “in the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit” (Mt. 28:19). Ambrose of Milan (c.600) pointed out that Jesus said, “In the Name,” not “in the Names.”

Looking briefly at just two other Trinitarian references, in Luke 10:21,22, we read, “At that very time (Jesus) rejoiced greatly in the Holy Spirit, and said, ‘I praise You, O Father, Lord of heaven and earth, that You have hidden these things from the wise and intelligent and have revealed them to infants. Yes, Father, for this way was well-pleasing in Your sight. All things have been handed over to Me by My Father, and no one knows who the Son is except the Father, and who the Father is except the Son, and anyone to whom the Son wills to reveal Him.’” And in II Corinthians 13:14 we find one of Paul’s most beautiful and frequently used benedictions: “The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ, and the love of God, and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit, be with you all.”

It is only when we try to put God in a test tube for an analytical study of His divine Personhood that we exceed the limits of our understanding. Artistic representations of the Trinity can speak to our hearts in profoundly helpful ways; yet they all fall short in various important respects. Let’s look briefly at just three such representations, two of which come from the Orthodox Church. One of the most famous of these icons is actually called, “The Divine Liturgy,” suggesting that all of Christian worship may be summed up in this single image (see below, The Divine Liturgy. Damaskinos, 1579-1584.)

While most icons are anonymous, this one in its original version is attributed to Michael Damaskinos, an artist working in a monastery on Crete about 450 years ago. Barely visible at the top is the Body of Christ, above and below which the words “Divine Liturgy” faintly appear in Greek. Surrounding the representation of the Holy Trinity are all the heavenly hosts, Cherubim and Seraphim, Thrones, Authorities, Dominions, Powers, Principalities, Archangels and Angels. The Body of Christ is literally carried at the top by a quartet of Authorities, and the chalice is being presented to Christ by 5 Dominions. The 6-winged seraphs below the Trinity carry incense burners and censers (thuribles), as well as the books of the St. Chrysostom and St. James liturgies.

But most important of course is the representation of the Godhead itself. The Father and the Son are seated on a throne behind an altar. Jesus is attended to by the angels who present the chalice and carry His Body. God the Father, as usual in Orthodox iconography, is presented as the Ancient of Days, dressed in the white robe of righteousness. His lower torso is turned to his left, but His head faces Jesus on His right hand, the place of special privilege and authority. Jesus is dressed as a Bishop, representing His relationship to His Church and His function as its High Priest.

The positioning of the Holy Spirit is of particular significance. The dove is flying towards the Father but is looking back at the Son, suggesting a very intentional compromise on the question of the Procession of the Holy Spirit as articulated in a famous theological document from a monastery on Crete during precisely the same period. Basically, in that Orthodox treatise, the Holy Spirit was said to have proceeded eternally from the Father but temporally from the Son when He promised to send it to his disciples and, by extension, to all believers. Thus according to this view, both the Eastern and Western understandings were true and acceptable without conflict. Damaskinos intentionally represents this compromise in his icon.

The second image is one to which I referred in a sermon a few weeks ago. It comes from a 12th century portal of the Basilica of St. Denis on the outskirts of Paris. Here God the Father holds the Son in His arms, or quite literally in His bosom, as the sacrificial Lamb of God, with the Cross appearing directly behind Him. The Holy Spirit once again is represented as a dove, this time hovering over and looking down on the Father and the Son. I personally find this to be one of the most emotionally powerful artistic representations of the Holy Trinity.

But it shares the same defect as the “Divine Liturgy” of Damaskinos: it can only show the three Persons of the Godhead in their separate manifestations, not in their eternal unity, which, of course, cannot really be imagined much less represented in painting or sculpture. In other words, the Three-in-One must never be defined as separate autonomous Persons even though they may be visualized that way.

The third representation I want to share with you comes again from the Orthodox Church and is among the most famous and widely imitated Trinitarian icons: it is the work of a Russian artist of the 15th century, Andrei Rublev, who died in 1430 and is canonized as a saint in the Orthodox Church. His icon, titled “The Holy Trinity,” has layers and layers of meaning despite the visual simplicity of its first impression. The Church long has interpreted these three angels to be a representation of the Holy Trinity. Rublev was the first iconographer to show them as being equal, both in age and in authority, each bearing an identical staff. Each wears different clothing, the Father’s being indistinct and almost transparent, representing the impossibility of looking directly on His heavenly glory. The Son wears the colors in which He is most often dressed in Orthodox iconography: a reddish-brown undergarment representing earth and His humanity, and a blue cloak representing heaven and His deity. By contrast the Holy Spirit wears the heavenly blue undergarment of deity and a cloak of delicate green, representing life and, in the Orthodox tradition, Pentecost. Above the Father is Abraham’s house, suggestive of the Father’s house; above the Son is the oak of Mamre representing the tree of life and perhaps the Cross; and above the Holy Spirit is a mountain (now only faintly visible), representing our spiritual ascent through the Holy Spirit to what the Orthodox Church calls “theosis.”

Many writers have tried to plumb the depths of meaning in this icon. It is the very first icon presented in Henri Nouwen’s book, Behold the Beauty of the Lord: Praying with Icons. Nouwen wrote, “For me the contemplation of this icon has increasingly become a way to enter more deeply into the mystery of divine life while remaining fully engaged in the struggles of our hate-and-fear-filled world.” That was in 1987! He added, “I knew that the house of love I had entered has no boundaries and embraces everyone who wants to dwell there.”

As for the content of the icon itself, Nouwen writes, “It is the mystery of the three angels who appeared at the Oak of Mamre, who ate the meal Sarah and Abraham generously offered to them and who announced the unexpected birth of Isaac.”

The story is found in Genesis 18, which begins, "The Lord appeared to Abraham by the oaks of Mamre, as he sat at the entrance of his tent in the heat of the day. He looked up and saw three men standing near him. When he saw them, he ran from the tent entrance to meet them and bowed down to the ground. He said, “My Lord, if I find favor with you, do not pass by your servant.” The passage continues with this same flipping back and forth between plural and singular, “they said, he said, Abraham said ‘Lord,’” etc. This very unexpected alternation of persons is precisely what has given rise to the Church’s understanding of these three persons as representing the Holy Trinity.

Returning to Henri Nouwen’s interpretation of the icon, he wrote: “The tree of Mamre becomes the tree of life, the house of Abraham becomes the dwelling place of God-with-us and the mountain becomes the spiritual heights of prayer and contemplation. The lamb that Abraham offered to the angels becomes the sacrificial Lamb, chosen by God before the creation of the world, led to be slaughtered on Calvary and declared worthy to break the seven seals of the scroll. This sacrificial Lamb forms the center of the icon. The hands of the Father, Son and Spirit reveal in different ways its significance. The Son, in the center, points to it with two fingers, thus indicating His mission to become the sacrificial Lamb, human as well as divine, through the Incarnation. The Father, on the left, encourages the Son with a blessing gesture. And the Spirit, who holds the same staff of authority as the Father and the Son, signifies by pointing to the rectangular opening in the front of the altar that this divine sacrifice is a sacrifice for the salvation of the world...

“As the mysteries of the intimate life of the Holy Trinity are unfolded to us, our eyes become more and more aware of that small rectangular opening in front beneath the chalice... it is the place to which the Spirit points and where we become included in the divine circle... its position in the altar signifies that there is room around the divine table only for those who are willing to become participants in the divine sacrifice by offering their lives as a witness to the love of God. It is the place where the relics of the martyrs are placed, the place for the remains of those who have offered all they had to enter the house of love.”

Nouwen concludes, “I pray that Rublev’s icon will teach many how to live in the midst of a fearful, hateful, and violent world while moving always deeper into the house of love.” The canons of the Stoglav Council (1551) encourage Orthodox believers not to look at the Icon as “the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit” – three individuals – but instead as the Holy Trinity: a Tri-Unity toward Whom our prayers are directed.

To summarize our understanding of the Holy Trinity we may say the following:

1) First with regard to the Son: all that Jesus was in the Incarnation was human (His humanity); all that Jesus was in the Incarnation was also divine (His deity). All that Jesus is eternally is divine (deity), eternally “begotten” of the Father, uniquely identified with Him in essential being (Ousia) and in substance (homoousios, consubstantialem Patri). When, in the Creed, we say that Jesus is “God from God,” we affirm His eternal generation from the Father. When we say that He is “Light from Light,” we are borrowing from Tertullian’s Trinitarian analogy of the emanation of light and heat from the sun: the Father is analogous to the sun, the Son is analogous to its rays, and the Holy Spirit is analogous to its focus. He also used the analogy of root, shoot and fruit. Tertullian (d. 240) was the first Church Father in whose extant writings we find the term “Trinity,” described as being of one substance (substantia), or fundamental reality, manifested in three Persons (personae). In Evensong, we sing the most ancient of all known Greek hymns, the Phos hilaron from c. 300. In it we praise the Son as the “gracious Light” Who is the “pure brightness of the everliving Father in heaven.”

2) And second, with regard to the Holy Spirit: all that the Holy Spirit is eternally is also of one being and one substance with the Father and the Son. When we come to the Holy Spirit in the Creed, regardless of what we say with regard to its “procession,” we affirm that the Spirit is rightfully addressed as “Lord” and as One Who, “with the Father and the Son, is to be worshiped and glorified.” John of Damascus, one of the Greek Fathers, wrote c. 700 that the Holy Spirit “proceeds” from the Father, but “rests in the Son” and is “communicated through the Son.”

All Christian worship is Trinitarian worship. The first words spoken in our Eucharistic liturgy, the Acclamation, are, “Blessed be God, Father, Son and Holy Spirit” except during Eastertide when we say, “Alleluia! Christ is risen.” And after every Psalm or canticle, whether in Morning and Evening Prayer, Compline or Holy Eucharist, we make the Trinitarian doxological statement, “Glory to the Father and to the Son and to the Holy Spirit.” When we make the sign of the Cross, while its primary focus is to identify us with Jesus Christ as His own people for whom He gave His life on the Cross, we also recognize that the sign itself has a clear Trinitarian aspect directly related to +Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Any time that a blessing is pronounced in Anglican worship, it is invariably a Trinitarian blessing. The Kyrie eleison is repeated three times; the Gloria invokes the Trinity in its text; the Creed is Trinitarian; the Sanctus and Trisagion have three repetitions of Holy, Holy, Holy; the Agnus Dei is repeated three times; and many prayers conclude with a formula such as “in the Name of Your Son, Jesus Christ, Who lives and reigns with You in the unity of the Holy Spirit, One God, forever and ever.”

On this Trinity Sunday, may we come to a clearer devotional understanding of what it means to worship in the Name of the Triune God; and through the testimony of Scripture and the visual aids provided in our iconography, may we be certain to give Him all honor and praise, in the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, Amen.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed