14 And the Word became flesh, and dwelt among us, and we beheld His glory, glory as of the only One from the Father, full of grace and truth. 15 John testified about Him and cried out, saying, “This was He of whom I said, ‘He who comes after me has a higher rank than I, for He existed before me.’”

29 The next day John saw Jesus coming to him and said, “Behold, the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world! 30 This is He of whom I said, ‘After me comes One Who has a higher rank than I, for He existed before me.’

43 The next day Jesus purposed to go into Galilee, and He found Philip and said to him, “Follow Me.” 44 Now Philip was from Bethsaida, of the city of Andrew and Peter. 45 Philip found Nathanael and said to him, “We have found Him of whom Moses in the Law and also the Prophets wrote—Jesus of Nazareth, the son of Joseph.” 46 Nathanael said to him, “Can any good thing come out of Nazareth?” Philip said to him, “Come and see.”

Christmas 2015: a homily for agnostics

John 1:14 And the Word became flesh, and dwelt among us, and we beheld His glory, glory as of the only One from the Father, full of grace and truth.

“The Word became flesh.” What does that mean? What could it possibly mean?

The surface meaning is obvious; we take it for granted. It speaks of the Incarnation, a baby born in a stable in Bethlehem, One Who is Emmanuel, “God with us;” One Who is Jesus, through Whom “God will save;” One Who is our righteousness, our hope, our companion, our friend, our Redeemer.

But what does that mean? How can we really even begin to fathom the eternal Word of God becoming flesh, taking on all of our human limitations, experiencing all our joys and sadness, accepting the excruciating self-sacrifice of a Cross, rising victoriously from the dead, ascending to the throne of God, interceding for each one of us, and waiting with divine patience for the moment unknown even to Him when the Father once again will say, “It’s time.” It was time 2,000 years ago for the incarnation: what Paul called “the fullness of time” in Galatians 4:4. And it will be time for Him to return to establish His Kingdom, the Kingdom that is from everlasting to everlasting, the Kingdom that will have no end, the new world that we call, “world without end,” when God Himself will be with us and He will wipe away every tear from our eyes (Rev. 21:3,4).

But what does that mean? How could we ever access these truths in a way that works for our inquiring and scientific 21st century minds? What does that mean?

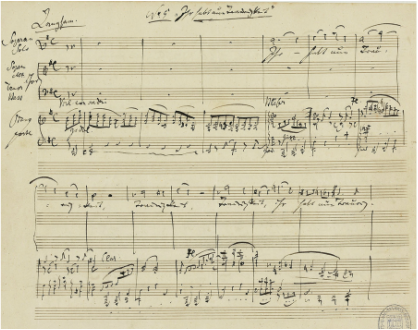

I had an epiphany this week: not the one that is coming up on January 6th, but one that relates profoundly to my long career as a professional musician. We have a relative who fervently believes that because of his long, illustrious and highly successful professional career, he now has a more profound understanding of Biblical truth than most other persons. But my epiphany went in precisely the opposite direction. I suddenly realized that my existence in what someone anonymously called “the cloud of unknowing” is just what has so richly enhanced my life as a believer.

I have made a number of references in past weeks to my “discovery” of icons and other works of Christian art as sources of devotional meditation on a different level from anything I have experienced in the past.

Let me explain by backing up a bit. In my decades as a professional musician, I cannot tell you how many times people have said to me, “I don’t attend very many classical music concerts because I don’t understand the music, I don’t have the hidden knowledge or background of study that would enable me to access what the music means.”

To such persons I always say the same thing. Even when they ask me to recommend a book they could read or a course they could take, I simply say, “Come and see. Sit quietly and let the music flow over you and around you. Close your eyes sometimes. Make not the slightest effort to ‘understand’ it. Just hear it and let yourself feel it. If you do just that simple thing, you will understand the music as well as any professional musician who has a degree in musicology or theory or performance. It really is that simple to discover what music means.”

You may think, “It’s easy for him to think such things, with his comprehensive knowledge of music.” But if that’s what you think, you have completely missed my point. What I’ve done in the past few days is to take myself outside the box of my professional expertise and put myself in other areas of mystery and perceived complexity. I’ve looked again at some favorite icons and other Christian art. In so doing I’ve realized that some, perhaps even most of the ones that have affected me most profoundly are also among the ones that I understand the very least from an intellectual and analytical perspective.

What do they mean? I admit that I may have no clue. What, precisely, was in the mind of the artist? Am I accessing his truth at all, or am I simply importing my more limited understanding of what the canvass might mean. What was the artist really saying? What am I seeing? Are they the same? Might they be radically different? And at the end of the day, does it really matter?

Let me use another example. In the past two weeks I have discovered the sacred poetry of someone of whom I had never previously heard: Malcolm Guite. I even ordered a book of his poetry and, in this age of almost instant gratification, Amazon had it on my doorstep the next day. I also have said several times recently that my favorite poet is George Herbert. But when I actually read a poem of Herbert or Guite and am deeply moved by it, I may go back to it and realize that I absolutely did not “understand” it or even try to access it intellectually, and whatever response I had to the poem may not have corresponded at all to what the poet himself intended or felt. And I have come to think that this is okay, that it’s every bit as acceptable as my asking uninformed persons to come and hear classical music without a hint of “insider knowledge.”

I found this epiphany to be quite liberating. It made me feel that it is actually okay for me to hear a piece of music, or stand in front of a painting or sculpture or read a poem or see a great play and go away having seen or heard or felt something absolutely profound, rivetingly worthwhile, deeply moving, and all the while perhaps not really knowing what it means.

What does the Incarnation “mean?” Will I ever have perfect understanding of it from the Author’s perspective? Will “the Word became flesh” suddenly become crystal clear to me? Will I be able more accurately to project the time that this babe of Bethlehem will return to establish His everlasting Kingdom? Will I suddenly have a clear picture of what that Kingdom will look like and where its geographic center will be? And if my answer is “no” to all of the above, should I withdraw from society to work it all out, while also studying art and literature and music in order better to understand what every masterpiece really means? Is this a fair parallel?

Yes and No. When I stand in awe in front of a work of art, or hear an astonishing piece of music, or read some amazing literature, I do not expect the Holy Spirit to enlighten my understanding in the same way that I expect the Spirit to help me understand Scripture. But perhaps the Holy Spirit expects me to suspend my disbelief when contemplating the greatest mysteries of all: what actually happened in the Incarnation; what actually happened in Bethlehem or on the Mount of Transfiguration or in Gethsemane or on Golgotha; precisely what happens in the Eucharist; or what’s coming next and when it will happen.

I will continue to ask my innermost questions at precisely the same time that I continue to proclaim God’s Holy Word. I will revel in the mysteries that Jesus Himself says are “hidden from the wise and prudent yet revealed to babes” (Mt. 11:25). I will continue to stand in awe at how newborn Christians can so quickly develop brilliant insights into God’s Word, how my own students at Moody were able to make observations that inspired me, how my seminary classmates sometimes could contribute more to my deepening understanding of God’s truth than could my esteemed professors.

This much I know for certain: “The Word became flesh and took up residence on earth, making His tabernacle among us:” from Bethlehem to the Cross to the Resurrection and Ascension; “and we beheld His glory, the glory as of the One Who was uniquely begotten of the Father’s love, the One Who fully realized all that is embodied in the concepts of grace and truth, of lovingkindness and eternal verity.” And He’s coming again, perhaps sometime soon.

What does this mean? What does it mean to you? Do you remember what I say to persons who are afraid of classical music? It is the same thing that Phillip said to Nathaniel after he had found the incarnate God, the One he identified as “Him of Whom Moses in the Law and also the prophets wrote, Jesus of Nazareth, the son of Joseph.” He simply said, “Come and see.” When we do come and see, then like Nathaniel we are able to respond, “You are the Son of God, the King of Israel.” And when we do that, in the truest spiritual sense, we will come closer to understanding the Incarnation, to knowing something of what it means.

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

The Collect

Almighty God, You make us glad with the yearly remembrance of the birth of Your Son Jesus Christ: grant that we, who have been born again and made Your children by adoption and grace, may daily be renewed by Your Holy Spirit; and grant that as we joyfully receive Him as our Redeemer, so we may with sure confidence behold Him when He shall come to be our Judge; Who lives and reigns with You in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever. Amen.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed