Our former rector at Church of the Holy Spirit in Lake Forest always loved to say that Trinity Sunday is the only Sunday in the Church calendar named after a doctrine, and he was more or less right. Accordingly this morning’s sermon will be uncharacteristically doctrinal. It’s clear that the doctrine of the Trinity was seen by the early Church fathers as a matter of greatest importance, as a touchstone of orthodoxy, of right faith. This is why all three of the major Church creeds, Apostles, Nicene and Athanasian, are Trinitarian in their very structure, and why the Athanasian Creed, the most detailed in its teaching regarding the Holy Trinity, is normally said on Trinity Sunday even if on no other occasion. It’s also the Athanasian Creed that most clearly spells out the doctrine of the two natures of Jesus Christ, another doctrine that was vigorously defended against a variety of heresies in the first decades of the early Church.

Athanasius himself was a fourth-century Father who was the most ardent and articulate defender of orthodoxy against the Arian heresy. Arianism asserted that Jesus Christ was granted sonship by God the Father at some point in time, and that He is therefore subordinate to Him. To those who crafted the Athanasian Creed within a century or so of Athanasius’ life, holding to all the truths stated in the creed was imperative. At both the beginning and the end of the creed, it’s stated that one cannot be saved without adhering to the Trinitarian doctrine taught in it. The creed calls this the “catholic faith,” and, as is often the case, it’s important to note that “catholic” has a lower case “c,” meaning orthodox, or more literally, “just as the whole,” those things on which the whole Church must be in agreement.

In our day, with our fierce egalitarianism and a concomitant distaste for anything that seems narrowly rigid, fewer and fewer Christians are willing to stand up for anything that is deemed catholic or orthodox. We don’t wish to be told that there are things we must believe in order to be saved, much less that someone else must believe those same things. In our attitude of “anything goes” theologically, we may be disinclined to worry ourselves about fine-tuning these doctrines. But this decidedly is not what is taught in Scripture or what has been held to be true by the Church for 2,000 years. And those very two things that are defended most forcefully in the Athanasian Creed, the two natures of Christ, fully divine and fully human, and the threefold nature of the Godhead, the Triune three-in-one, remain at the very core of what Christians must believe.

Some of you may be thinking that this is more than you ever thought you had bitten off when you joined yourself to the Christian Church. While you won’t find me backpedaling on this, I will make haste to say that both doctrines contain a large element of mystery that cannot be reduced to simple formulas. This is precisely why both the Jewish faith and the Christian faith must be called “faiths” in the first place. As long as God has spoken in various ways and in assorted times through His prophets to reveal His nature and actions and standards, there have been those who believe, as well as those who refuse to acknowledge Him. The doctrine of the Trinity has been called the “central mystery of [our] faith” (Catechism of the Catholic Church 234). But labeling anything in our faith as “mystery” doesn’t mean we should set it aside as something inscrutable, irrelevant or inconsequential. In fact, in Biblical usage “mystery” most often refers to something that has been specially revealed to us through the Holy Spirit.

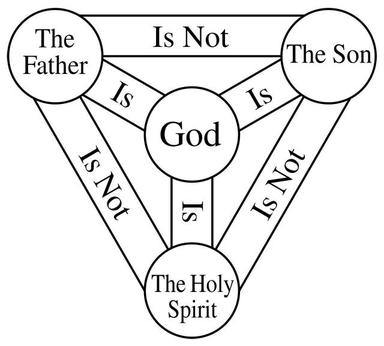

Because this is Trinity Sunday and because it’s a Sunday named after a doctrine, we need to do our best to wrap our heads around what it means for God to be “three-in-one.” All sorts of analogies and graphics have been put forward to explain the mystery of the Trinity, and every one of them falls down at some point [St-Denis]. Athanasius himself is credited with devising a triangle to represent what each Person of the Trinity is and what each is not. We looked at this model in our first catechism class. It certainly is among the best models we have; but it’s not perfect. It defines the unity and the separation, but not the functions or the importance of God making Himself known in this way.

Following Athanasius, the starting point for understanding the Trinity is to take care in defining what it is not. It is NOT tri-theistic; Christianity is through and through a monotheistic faith that recognizes the One God of the Hebrew faith. Every Christian could retain the Jewish custom of rising every morning and reciting the Shema from Deuteronomy 6: “Shema Yisrael, Adonai Elohenu, Adonai echad: Hear, O Israel: the Lord our God, the Lord is One.” But we also believe that God became incarnate in the Person of His Son, Jesus Christ, in order to redeem the world from sin and death through His sacrifice on the Cross and His Resurrection from the dead. We also claim the promise of Jesus to send us the Holy Spirit, the Comforter, to mediate His continual presence with us, to serve as our Advocate, to remind us of His teachings and to empower us to be His witnesses. Taking together the many Biblical references to all three Persons of the Holy Trinity that provide more than enough confirmation of the doctrine itself, we can affirm that the Church got it right not only theologically but also practically: we believe in One God, Who is manifested to us in three Persons, co-equal, co-eternal, to be worshiped and glorified now and forever. To the abundant Biblical evidence may be added a plethora of quotations from the earliest Church Fathers.

How can we understand this better in simple terms? We have 2,000 years worth of suggestions and approximate analogies, all of which may rightly be subjected to criticism or outright refutation. 3-in-One Oil was originally formulated in 1894. Its name, given by the inventor George W. Cole of New Jersey, derives from the product's triple ability to "clean, lubricate and protect." This gives us a very fascinating model of the Trinity: one substance (a word and concept at the very center of Trinitarian doctrine in the early Church), and three distinct functions. I will resist distinguishing how the three Persons of the Trinity can “clean, lubricate and protect” us, though it’s tempting to try. But as clever as this model seems, it would be rejected by some as heretical.

St. Patrick, one of the three patron saints of Ireland, famously defended the doctrine of the Trinity by analogy to the shamrock, a sort of three-leaf clover, one leaf but with three distinct and equal divisions. Soon we will be meeting in a church that bears his name. It has a huge St. Patrick stained glass window in the rear, and it will be important for us to acknowledge his contributions to the spread and defense of our faith. [Show St. Patrick’s “window.”] Patrick lived at about the same time that the Athanasian Creed was being formulated and is credited with writing the poem known variously as “St. Patrick’s Breastplate” or “The Deer’s Cry” or the “Lorica of St. Patrick.” It both begins and ends with this verse:

I bind to myself today

The strong virtue of the Invocation of the Trinity:

I believe the Trinity in the Unity

The Creator of the Universe.

Gayle has strong memories of three mimes who perfected a routine where they moved in precise parallel motion, trying to represent the Trinity in the unity of the Godhead. Others have used the sun as an analogy: one substance, but from it emanates both light and heat, an imperfect analogy that works perfectly for some while others find it dangerously heretical. It’s the same with the egg: yoke, white and shell: decidedly imperfect, but helpful to some.

Even if we were to roll all these attempted representations together, we could not wholly grasp the concept of a God Who, being of One substance (homoousios), exists eternally as Father, Son and Holy Spirit. The persons who put together the Revised Common Lectionary had us reading the entire creation story today from Genesis 1 through the first verses of Genesis 2, just so we would hear these words: “Let Us make man in Our image, according to Our likeness” (1:26), words that have been taken to indicate the participation of the entire Godhead in the work of creation. Certainly we start out with “the Spirit of God moving over the surface of the waters” (1:2) and we have the Apostle John writing that without the Word, Jesus Christ, “was not anything made that was made” (John 1:2). Paul adds in Colossians 1, 15 “He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation.16 For by Him all things were created, both in the heavens and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or authorities—all things have been created through Him and for Him. 17 He is before all things, and in Him all things hold together.” The author of Hebrews adds, “(The Son) is the radiance of (the Father’s) glory and the exact representation of His nature, and upholds all things by the word of His power” (1:3).

Like Gayle’s mimes, the three persons of the Trinity work together in perfect unison, yet they remain distinct in Person and function, and operate individually in terms of the economy of the Godhead. Just two Sundays ago we looked at the magnificent intercessory prayer of Jesus for us in John 17, where He asks the Father 21 “that they may all be one; even as You, Father, are in Me and I in You, that they also may be in Us, so that the world may believe that You sent Me. 22 The glory that You have given Me I have given to them, that they may be one even as We are one, 23 I in them and You in Me, that they may become perfectly one, so that the world may know that You sent Me and loved them even as You loved Me.” It was the desire of Jesus that in some real way we would enter into the very unity of the Godhead so that this unity would demonstrate God’s love to the whole world.

Here we’re reminded of two things: one is that when we try to reduce the character of God to a single word, invariably it will be “love,” as John wrote in 1 John 4:8, 16. And we cannot conceive of love in any completely abstract form: love demands an object for its expression; it has to be directed towards someone. The Trinity bears witness to the fact that from the beginning God existed in a loving fellowship as Father, Son and Holy Spirit. The creation of humankind as male and female, stated to be in the Image of God, is an illustration of the fellowship within the Godhead. Marriage is another Scriptural analogy, where two become one. Similarly the unity of the Church as the Body of Christ is meant to represent a fellowship reflecting that of the Godhead while fulfilling the intercessory prayer of Jesus. Both love and fellowship are at the heart of Who God is and how God acts relationally.

Where we go off the rails in trying to wrap our heads around the concept of the Trinity is when we try to reconcile our ideas of functional diversity and subordination with co-equality. This is because there’s no human analogy that holds up to such scrutiny. Whether we think in medieval terms of a king, his crown prince who is heir to the throne, and his chancellor who wears his seal and represents him to the realm; or in contemporary terms of a business owner, his CEO and his CFO, we are dealing with differences of persons based on inequality of rank and function.

But this is not so in the Godhead. We must remember in the first place that the many statements of Jesus about saying only what He hears the Father saying, doing only what He sees the Father doing and, especially, declaring that “the Father is greater than I,” all were made during the Incarnation, when Jesus, the Son of God, became the God-man, having emptied Himself of His divine prerogatives to take on human form, even that of a bondservant. He was voluntarily and temporally submitting Himself to the will of the Father. Read John straight through, and this will become clear.

When we say that the Holy Spirit “proceeds” from the Father and the Son, we may think of the medieval chancellor or perhaps of the modern Secretary of State or the Public Relations executive, persons who have a very subordinate role that is far from co-equal with their superiors. But when it comes to the Godhead, functional diversity does not imply inequality, whether or not that “makes sense” to us. This is where most of the humanly devised analogies we use to represent the Trinity fall short. We simply don’t have any perfect analogy. The best one is the Shield of Athanasius, also known as the Scutum fidei, “the Shield of Faith,” precisely because it doesn’t address the functional economy at all!

So what are we to do? We’re to exercise faith, which is precisely why the triangular representation of Athanasius is called a “Shield of Faith.” We are to allow room for mystery, acknowledge our limitations, recognize that God, in the Judaeo-Christian faith is indeed “other,” and accept that God alone can exist in one substance yet three co-equal and co-eternal Persons, each of Whom functions in ways that suggest subordination without surrendering equality. As we sometimes say, we need to “let God be God:” let God be an infinite Being while we are finite beings [show page]. Paul put it a bit more forcefully in Romans 3:4 when he wrote “Let God be true but every man a liar.” The context was different but the principle was the same: we need to acknowledge that in many areas, the truth of God lies just beyond our grasp. A. W. Tozer called this “the language of true faith” [show page]. Our analogies in words and pictures often help us to get closer to understanding God’s mysteries, yet at other times they may be misleading or even heretical. But when it comes to understanding the Holy Trinity, Athanasius with his Shield of Faith and the confession that summarizes his teaching gets us as close as possible. And for that we can say “thanks be to God.”

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, Amen.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed