Here is another Sunday when the lectionary readings are so rich and varied that deciding what to include or what to leave out is a delightful challenge. More than one theme can be seen weaving its way through these passages and it’s severely tempting to chase after all of them. Alas, I have to stop short of saying “time permitting,” because time never does permit in such a circumstance. And so, being forced to make a decision, I opted in favor of an oblique theme that seemed to beg explication: “defending and living the faith,” with a subtitle of “what works and what doesn’t.”

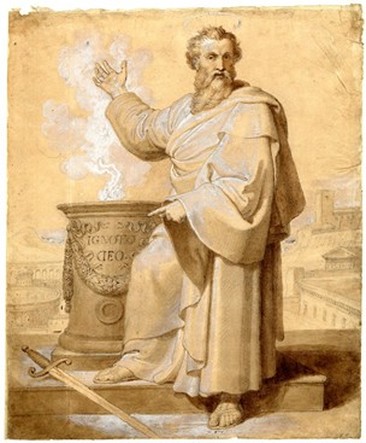

Taking our readings in order, we’ll look first at the discourse of Paul in Acts 17, one that has fascinated me as long as I can remember. It’s a real one-off: Paul uses an approach that we never find him using again, he uses it in a city to which he will never return, he leaves without establishing a church, he never writes an epistle to the Athenians, and he utterly abandons this methodology. We may even wonder why Luke chose to include this pericope at all other than because he was tracing Paul’s footsteps on his missionary journeys.

So what was this failed approach and methodology, and what should we learn from it? It seems to be the one and only instance in Scripture where an ad hominem argument is used with an appeal to practitioners of a pagan religion complete with a quotation from a pagan poet. Why has this always fascinated me? I suppose it’s because it shows a side of Paul that we will never see again. Maybe the setting in Athens, the home of numerous Greek philosophers and orators, inspired the brilliant Paul to try his hand and strut his stuff as an apologist. I suppose that all great apologists try to use the ad hominem approach, that is, to start where the listeners are as the home base or the ground for moving on to something new. As Luke notes parenthetically and perhaps sarcastically, the Stoic and Epicurean philosophers in Paul’s audience were naturally enamored of anything new and were at least somewhat eager to hear Paul out. He certainly was teaching something completely unknown to them, and already they were finding it a bit bizarre, “strange to their ears,” especially the bit about a Resurrection.

And so Paul begins on their ground, complimenting them on their religiosity and their covering of all the bases with an altar “to the Unknown God.” Evidently Paul thought he could dive into that vacuum and persuade them that his Judaeo-Christian faith was their missing link. He then launches into a presentation of monotheism, a Creator God who is not worshiped with idols of any sort, a transcendent Being Who is Lord of all people but Who also is immanent, close at hand for all who seek Him. Paul then issues a call to repentance, something we find in the preaching of John the Baptist, of Jesus Himself and of Peter in both of his first sermons in Acts 2 and 3. But it’s when he makes the decisive claim of the Resurrection of Jesus from the dead as proof of his proclamation that Paul seems to lose many of his hearers. Our lectionary stops just short of Luke’s observation that some of Paul’s hearers sneered, perhaps the same ones that had labeled him an “idle babbler” before he even began this speech; others suggested that they might need to hear more on another occasion, and only a few persons responded positively. This was a far cry from the three thousand who responded at Pentecost and from the successful church planting that Paul was able to do in many other places.

We’re left on our own to figure out why this was such an unsuccessful venture. Some simply blame it on an unreceptive and pre-prejudiced Athenian audience. Others more optimistically suggest that the few who accepted Paul’s message may in fact have established a church after Paul’s departure, though we never hear of such a church until well after the New Testament era. In any event, the fact remains that Paul abandoned this methodology, never returned to Athens and in his later writings only once even referred to having stopped at Athens (I Thessalonians 3:1).

What we need to notice on the positive side is that the focus of Paul’s preaching in Athens was the very thing that his hearers rejected: the Resurrection of Jesus coupled with a call to repentance. We are reminded at once of these same emphases in Peter’s sermon at Pentecost where, after twice affirming that God raised Jesus from the dead, he calls on his hearers to “repent and be baptized in the Name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins, and you shall receive the gift of the Holy Spirit” (Acts 2:24, 32, 38).

Repentance is a singularly unpopular concept in our time, not only among the unrepentant unbelievers who reject the very concept of sin from which repentance is required, but even more insidiously among many Christians themselves who seem to have retreated into a medieval monastic notion that repentance is a one-time thing. It may surprise many of you to know that for Martin Luther, this was the very starting point of his charges against the Catholic church of his day. This year is the 500th anniversary of Luther’s 95 theses, still regarded by many as the inaugural and seminal event of the entire Reformation. It has given many evangelical scholars, writers and teachers a fresh opportunity to re-examine precisely what it was that set Luther on a different path from the one he had pursued as a Catholic clergyman.

Do you know what the very first of his 95 theses taught? Here it is: “When our Lord and Master, Jesus Christ, said ‘Repent,’ he meant that the entire life of believers should be one of repentance.” What!!?? Again, “When our Lord and Master, Jesus Christ, said ‘Repent,’ he meant that the entire life of believers should be one of repentance.” How far have we drifted away from that concept! Might that not be part of why the Church has lost its power, a power that was so strikingly evident at Pentecost and in the Reformation, a power once so great that it transformed the Roman world in the early centuries of the Church and transformed all of Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries?

Luther, out of his immersion in a culture that elevated the traditions of the Church above the authority of Scripture, discovered that the gospel called not for an act of penance but for a life of penance: not an indulgence for sin that could be purchased from Rome, but a radical change of mind-set, a deep transformation of life, and an acknowledgment that “the entire life of believers should be one of repentance.” As the Scottish Presbyterian preacher and scholar, Sinclair Ferguson, has written, “evangelicals need to reconsider the centrality of repentance in our thinking about the gospel, the church and the Christian life.” He added, “It is sad that evangelicals have often despised the theology of the confessing churches. It has spawned a generation who look back upon a single act, abstracted from its consequences, as determinative of salvation. The ‘altar call’ has replaced the sacrament of penance. Thus repentance has been divorced from genuine regeneration, and sanctification severed from justification.” That’s a leading evangelical Presbyterian writing, not an Anglican!

The point here is that we need to spend much more time on our knees. And it may well be that only in that spiritual posture of repentance will we recover the power of the Holy Spirit that was unleashed at Pentecost and in the great revivals of the 18th and 19th centuries. At Pentecost, Peter preached “repent and be baptized.” And 30 years later, writing to his flock, Peter wrote words that only puzzle us if we’ve lost sight of what he meant in the first place: “Sanctify Christ as Lord in your hearts and keep a good conscience. Baptism now saves you by an appeal to God for a good conscience through the Resurrection of Jesus Christ, Who is at the right hand of God, having gone into heaven, after angels and authorities and powers had been subjected to Him” (I Peter 3:15a, 16a, 21, 22).

Here we have Peter doing precisely what Sinclair Ferguson says we have ceased to do as evangelicals: far from severing repentance from regeneration, or sanctification from justification, Peter is lumping them all together in a powerful and exegetically brilliant way: the sacrament of baptism has its saving power when we appeal to God for a good conscience, which is what repentance is all about; and we know that this is possible because, by the victorious power of the risen and ascended Christ, we are justified and we are being sanctified even as we sanctify Christ as Lord in our hearts and keep a good conscience. See how the mystery dissolves when we take the gospel message as a whole piece of cloth rather than trying to untangle each of its pieces in isolation from every other! That was indeed the medieval mistake that Ferguson fears is finding a resurgence in contemporary evangelicalism.

Are you ready to cry “uncle?” Are you wondering how on earth it’s possible to live up to all that these Scriptures demand of us? Do you feel the need for some supernatural help here? I know I do! But guess what? Supernatural help is readily available. That’s the message of Jesus to His disciples in today’s Gospel reading. It’s definitely a tough love message; but it comes with a fail-safe mechanism for making it happen.

I’m getting a bit ahead of myself, but that’s intentional. I’m trying to stave off your terror before I return to those daunting words: “If you love Me, you will keep My commandments.” “He who has My commandments and keeps them is the one who loves Me. “If anyone loves Me, he will keep My word.” “He who does not love Me does not keep My words.”

If you don’t find this message daunting, it can only be that you have an inadequate knowledge of what the words and commandments of Jesus require. I could cut to the chase and remind you of something Jesus said in the Sermon on the Mount: “You must be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect” (Matthew 5:48). When I preached from this passage some weeks ago, a dear friend who was visiting that Sunday later wrote that I had scared him to death with those words of Jesus! According to the Apostle Peter, my friend’s response was the right one. In his first letter, Peter wrote, “As He who called you is holy, you also are to be holy in all your conduct, 16 since it is written, ‘You shall be holy, for I am holy.’ 17 And if you call on Him as Father Who judges impartially according to each one's deeds, conduct yourselves with fear throughout the time of your exile (on earth)” (I Peter 1:15-17). Fear is an appropriate response to the demands of following Jesus.

How did the Apostle Paul measure up to the standard of perfection in holiness? Paul wrote to the Philippians, “12 “It’s not that I have already obtained this or am already perfect, but I press on to make it my own, because Christ Jesus has made me His own” (Philippians 3:12, ESV). “I press on to make it my own, because Christ Jesus has made me His own.” There’s a great antidote for fear: Christ Jesus has made me His own! And there once again we see justification and sanctification rolled together in Scripture. And again we acknowledge with Luther that “the whole of the Christian life is repentance.”

Am I leaving something out? Yes, I saved the best for last, again intentionally. Jesus, speaking to His disciples in the Upper Room on the very eve of His arrest in the Garden, says, “I will not leave you as orphans; I will come to you!” (John 14:18). How will He keep that promise when in fact He’s about to be arrested, tried, crucified and buried? And, even though He will rise again, He will ascend to the right hand of His Father a mere 40 days later. But He had already given the answer to the question when He said, “I will ask the Father, and He will give you another Helper, that He may be with you forever; that is, the Spirit of truth. You know Him, because He abides with you and will be in you” (John 14:16, 17).

Did you get the “forever” part of that? Therein lies our comfort and assurance. The very One that Jesus calls our “Helper” is also our “Comforter,” the One Who continually and eternally assures us of His abiding presence. This also is the key to the statement Jesus makes later in this passage, “If anyone loves Me, he will keep My word; and My Father will love him, and We will come to him and make Our abode with him” (vs. 23). It’s the Holy Spirit Who mediates the presence of the Father and the Son to us until that great and glorious day when we will be forever in the very presence of God the Father and God the Son. Until then, we have the One Who is called alongside to help and comfort, the Holy Spirit, Who is also our Counselor and Advocate.

Could we ask for more? What does Jesus ask of us in return? That we show our love for Him by keeping His commandments and keeping His word. This is not the easiest of tasks, but it can be an immensely rewarding one. And to that end we are not left as orphans: rather, we have a Helper Who will be with us forever.

To the Triune God, the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, be all honor and glory and praise both now and forever, Amen

RSS Feed

RSS Feed